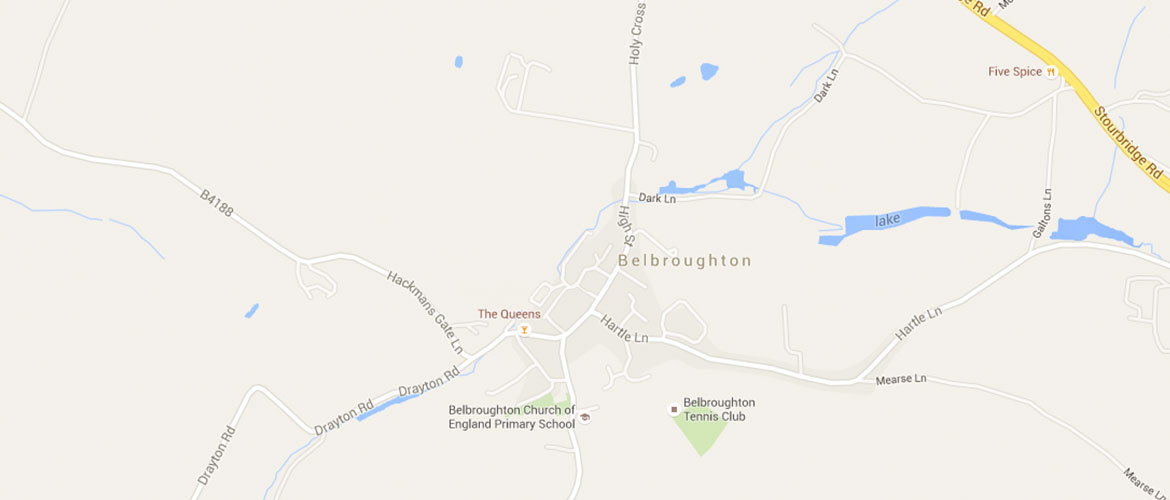

Nestling in a valley on the lower slopes of the Clent hill range lies the village of Belbroughton, about seven miles south of Stourbridge. Through the centuries the village has been known by a variety of names, including Broctune, Belne, Bellem, Bryan’s Bell and Bellenbrockton before finally becoming Belbroughton.

Belbroughton is a village and civil parish in the Bromsgrove District of Worcestershire, England and once was at the core of the North Worcestershire scythe-making district.

The earliest mention of the village was in AD817 but there could have been an earlier settlement. In 1086 there was already a priest and a Saxon church, which stood on the same site as the present Holy Trinity church. The church was later rebuilt by the Normans and some remnants of this structure still remain. The church has been altered over the years with large scale restorations in the 1890s. The tower clock was erected in celebration of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee and the lychgate was built in 1912 and dedicated to Henry Charles Goodyear, a missionary from the parish.

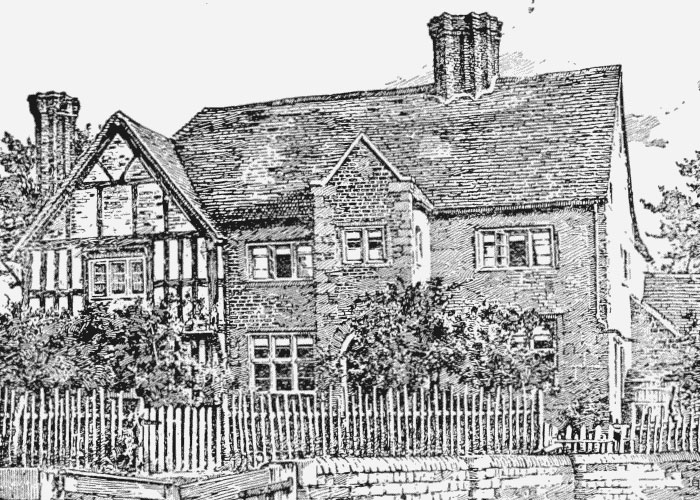

Holy Trinity, Belbroughton is a “Doomsday Book” Church; a fine medieval building with a long and worthy history. The present Churchyard may be the site of early Pagan religious ceremonies, The base of the existing Woodgate memorial is believed to be a Pagan preaching stone. After conversion to Christianity, it is thought a wooden Church was erected, to be replaced in Norman times with a substantial stone structure. Little of this remains but there is a Norman Chapel in the grounds of Bell Hall. The present Church was built at the beginning of the 14th Century but the Black Death of 1348/9 had a devastating effect on all activity and claimed the lives of three Priests. The Church at that time was highly decorated and traces of the original colours can just be seen.

Despite all the new houses built in the village during the last 30 years there are fewer inns and shops serving the village today than in the 19th century. At one time there were at least 11 inns and alehouses but today only four remain. The Bell Inn, the oldest, and recorded as belonging to Sir John Conway in 1580, The Talbot Hotel and the Horseshoe Inn at the village square have survived along with The Queen’s Hotel at the lower end of the village.

Belbroughton’s sons and daughters have, over the years, emigrated to the far corners of the world. In 1787, one Sarah Bellamy, set sail for Australia, alas not of her own volition. Sarah, a 15 year old servant girl, was convicted of stealing a linen purse and money and sentenced to transportation to Australia, sailing with the First Fleet, and spending the rest of her life there.

In this part of rural Worcestershire there was always a pressing need for edge-tools for agricultural work, and especially for that great leveller of corn and grass, the hand scythe. Such sharp edges could not be made easily by hand; they needed grinding on a mill stone; and that mill needed power to turn it.

The source of power for Belbroughton’s mills came courtesy of the Ram Alley or Belne Brook, which plunges down from the Clent Hills to join the River Stour at Kidderminster. The Brook passes by the Old Nash Works (now occupied by a new set of offices called Mill Pool) it runs under the bridge leading to the stables and fields and cascades down into the culvert that runs underground beneath our Secure Storage Units in Nash Lane reappearing at the side of The Queens public house.

A whole series of mills tapped the brook’s waters from at least the 13th century, gradually switching from corn milling to metal grinding as the industrial revolution began to take off.

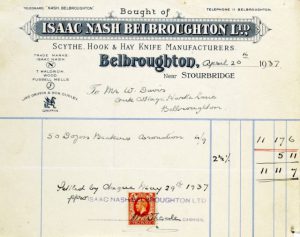

The man who, more than any, laid the foundation for Belbroughton’s supremacy in scythe making was Isaac Nash, who also brought Black Country expertise into the village. Nash served his apprenticeship as a forger and plater in Dudley, before moving to Belbroughton to take over Newtown Forge in 1840.

At this time the Belbroughton mills worked in combination, one worked doing the forging or plating, and another the grinding and polishing. Isaac Nash was the first to achieve vertical integration, taking over neighbouring mills so that he could combine the whole process. By the 1880s Nash owned or rented some eleven mills and forges in the area, and was employing more than one hundred workers.

The Grim Reaper finally came for Isaac Nash in September 1897, no doubt wielding a locally-made scythe, but the firm’s future was secure, at least for another half-century.

Isaac Nash put Belbroughton scythes on the international stage, supplying blades across the Commonwealth, as well as to the United States, South America and parts of Europe. Danish farmers alone bought some 10,000 a year. Yet curiously many of the Nash exports bore the trade name “Thomas Waldron”, the man that had started the industry in the first place. When Nash bought out Waldron’s, he purchased the right to retain their name.

Bear in mind that different parts of the world, as well as different counties in England, preferred scythes of a particular design, varying greatly in length and thickness. In addition, different plants – whether they be mint, lavender, hay, grass, hedge and even peat – required handles and blades of variable length and thickness. The Belbroughton scythe-makers had to meet all of those many particular demands.

What made the Nash scythes and sickles the industry leader was the way in which they were put together. While cheaper blades could be made from a single piece of steel, the Belbroughton scythes consisted of a layer of metals. On the outside were two thin strips of Swedish iron (considered to be the best in

Europe), and sandwiched between them was the sharp cutting steel, which was supplied from Sheffield.

Such a blade went through a complex process of welding together and forging, before it was tempered and hardened. Then, when the scythe was ground, the cutting steel was exposed. The Belbroughton blade was thus more easily sharpened, and less prone to breaking than its less robust rivals.

It was ironic that the mechanisation which had stimulated the Belbroughton industry was eventually the cause of its downfall, as agriculture shifted from hand-operated cutting to mechanical harvesting.

In the wake of such changes, Nash’s diversified into other areas, supplying butcher’s knives and palm cutting equipment to Africa, but slowly the mills fell silent. The firm was taken over a number of times in the 1960s, ending its days as part of Spear & Jackson. In April 1968 the works came to a grinding halt.

Most visitors to Belbroughton today would have no idea that it had an industrial past, and there is little in the village today to give any hint of its significance. A few of the old mill pools survive, but most of the mills themselves have been demolished.

You can add Belbroughton scythes to that long list of lost industries of the West Midlands.

Today, Belbroughton is becoming known for its Beer and Musical festival, one of the country’s biggest beer festivals. It’s also famous for the Belbroughton Scarecrow Festival which takes place every year raising thousands of pounds for charity and bringing thousands of visitors to the village.